Great Expectations

Optimistically we swallow the tablet, because it helped last time. Or we take one for the first time and are upset to read its potential side-effects. In either case, our expectations differ hugely – and maybe as a result the effects of the same medicine do too.

By Birte Vierjahn

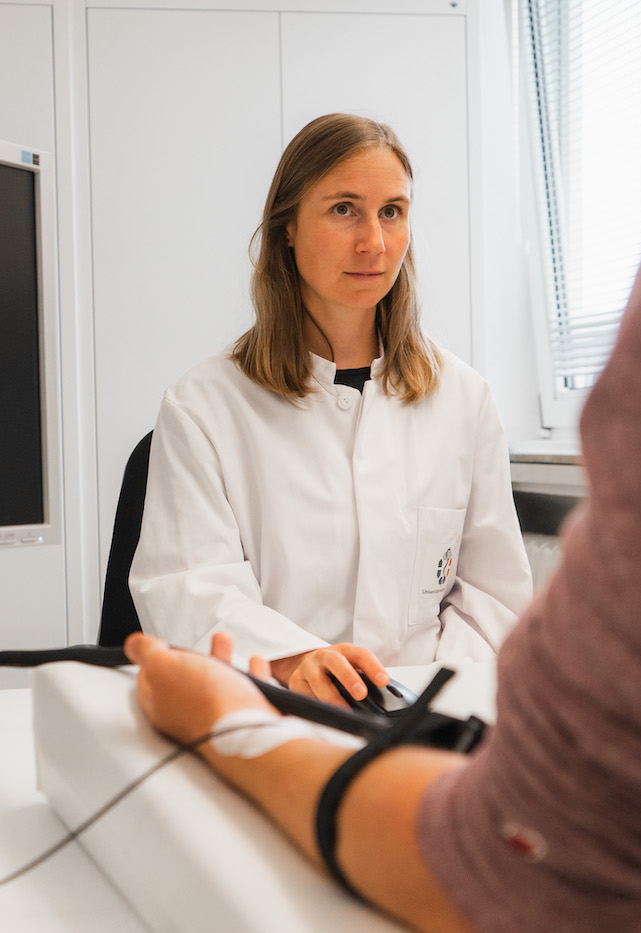

One leg loosely crossed over the other and tapping his toe, the 20-something volunteer faces the doctor across the table. Attached to the inside of his lower arm, which rests on a wedge pillow, there is a device the size of a playing card.

The young man is taking part in a study by the Clinical Neurosciences and Translational Pain Research Department at University Medicine Essen. The team headed by its director, Prof. Dr Ulrike Bingel, is looking at the interaction between pain and cognitive processes. It’s a broad field, stretching from molecular mechanisms to subjective psychological processes (see box).

At the heart of the Bingel Lab’s current research is the UDE-based Collaborative Research Centre/Transregio 289, for which Bingel herself acts as speaker. The researchers study the effects triggered by expectations in patients being treated for pain or depression. Their work focuses on the placebo effect, defined as a positive health effect which arises simply from the assumption that a specific treatment will help. ‘The placebo effect is often the baddie in clinical studies because it can jeopardise the introduction of novel drugs. We’re looking at it from the other side: we want to use the effect by adding it to the pharmacologically effective treatment, like the cherry on the cake,’ says Bingel of the group’s objective, ‘Therefore we are studying how expectations affect the body, so that we can use them as a booster in therapy.’

THE BINGEL-LAB

The research group headed by Prof. Dr Ulrike Bingel studies pain from a neuroscientific and psychological perspective, with the aim of applying the findings in daily clinical practice. This demands not only interdisciplinary cooperation but also a high degree of medical and research expertise, so the research group comprises neurologists, neuroscientists, psychologists, biologists and computer scientists. The research group is also affiliated with the Erwin L. Hahn Institute, whose 7-Tesla MRI scanner delivers extremely high resolution cross sections of the brain and nervous system to aid in pain research.

Now the young man briefly closes his eyes and draws his brows together. He isn’t tapping his foot any more. He sits upright, his body seems tense.

Pain can be triggered in the tissue at the free nerve ends, but ultimately evolves in the brain. Every ‘OW!’ stems from a balance of pain-inducing and pain-inhibiting endogenous stimuli. This complicated cascade can be affected by prior experience, both positive and negative. If we have positive expectations – because a medicine helped us last time –, this triggers our evolutionary pain inhibition. Endogenous opioids are released, and there are indications that the neurotransmitter dopamine is involved. There are complex cascades of signals, which can already be seen in the spinal cord to place an active brake on the pain.

PLACEBO’S EVIL TWIN

There is however also a contrary effect: the nocebo effect. In this case, patients assume that the treatment will not work or even that it could be harmful. The roots of these negative assumptions can lie in something as simple as a normal package insert that has pages setting out side-effects ranging from rashes, nausea, and allergic reactions – even leading to death – in clinically factual terms, yet only dedicating one sentence to the benefits of the medicine. Subsequently, negative symptoms can actually occur that cannot be explained pharmacologically.

Package inserts are like a turbo-trigger for nocebos,’ Bingel comments, and so she is determined to change this. She wants to create positive expectations and avoid the occurrence of unnecessary fears: ‘First I want to read why I should take it. “This medicine prevents one heart attack in ten,”’ Bingel gives as an example. ‘In addition it helps many people if they under-stand the response to an active ingredient in their bodies. This can be incorporated using links to videos or other more in-depth information. And finally it’s important to present the occurrence of side-effects from another perspective. At present, it states “Nausea: very common” for one person in ten who gets nauseous. So just ten percent! “More than 90 percent tolerate the medicine perfectly fine” would be a far more worthwhile statement for the mental and physical effect.’

TREATMENT EXPECTATION

What effects do patients’ positive and negative expectations have on the success of a treatment? In the transregional German Research Foundation (DFG) collaborative research centre (CRC/Transregio 289) entitled ‘Treatment Expectation’, an interdisciplinary team is drawing on basic research and on clinical practice in 16 subprojects investigating aspects of this question. Together with colleagues from Marburg and Hamburg, UDE scientists aim to decode the underlying neurobiological and psychological mechanisms, record individual differences and transfer the results into daily clinical practice. The CRC/Transregio is headed by Prof. Dr Ulrike Bingel.

The volunteer relaxes visibly, thinks for a moment and enters ‘76’ in the computer in front of him. The study is confidential and in fact far more complex than depicted here, but the basis of the experiment is that unpleasant heat stimuli are applied to the volunteer’s lower arm. The temperature varies, and each stimulus lasts 20 seconds. Then the volunteer records how painful he found the stimulus, using a scale of 0 to 100.

Compared to the placebo effect, the effect of nocebos is far less well understood. Despite numerous studies into pain, the proportion of publications is 100:1 for the placebo effect. Although it is already known that some people are especially sensitive to the effect of expectations and others less so, it is still unclear whether this is also linked to their nocebo response. One reason for the lack of knowledge about placebo’s evil twin is an ethical dilemma: to provoke a nocebo response, subjects have to agree to join the study and develop a negative point of view. Although they do not receive any harmful treatment, participants could ultimately feel physically or mentally worse – simply because of their negative expectations. There is a fine line here, ethically and clinically, particularly when wanting to study these important effects in patients.

A brief break in the experiment: the young man sinks back in his chair and looks at the doctor as she prepares for the next cycle. She opens a wall cabinet on his left, where medicines, gloves, disinfectant and other medical utensils are stored neatly and conveniently to hand. Somewhere in the room a fan hums, but otherwise it is quiet – even in the hallway outside the room. With practised hands, the doctor pulls on the gloves and opens a white tube: ‘Before the next series of tests, I’m going to apply a soothing cream. This is a normal anaesthetic. It should result in you perceiving the heat as less painful.’

EFFECT = MEDICINE + EXPECTATION

Depression and chronic pain are the diseases of the day, and cost society dearly. At the same time, we know that expectations can influence subjective symptoms such as pain, tiredness and negative mood extremely strongly: as the Botox example shows, in both chronic pain and the treatment of depression often more than 50 percent of the outcome is down to the effects of expectations and not the pharmacological treatment itself.

‘Doctors are paid least for “just” listening to patients and sympathising. Yet this can work wonders,’ explains Bingel. ‘There needs to be far more about communicating well and meaningfully in medical training. This is also the case for pharmacists, who usually only talk about potential side-effects and safety risks.’

The cream has been absorbed, the next cycle begins. The doctor precisely applies a sequence of temperatures which the volunteer earlier rated at 40, 60 and his previous maximum level of 76. The first stimulus: less painful than before treatment.

So how can expectations and pharmacological treatments be combined? Empathic instructions and a reassuring setting can play a large part: the doctor describes the effect of a treatment in clear, factual terms, has a professional appearance, is appropriately dressed, conveys a sense of authority with their spoken and non-verbal communication. The room is clean and equipped with medical instruments and reference books, perhaps there are certificates and official qualifications on the walls. In brief: it looks, sounds and smells how a medical facility should.

The pain grades are consistently lower, the volunteer seems more relaxed. An effect of the cream? Familiarisation? Expectation? The young man does not know whether he really received a soothing cream. And since this is a double-blind study, neither does the doctor who is carrying out the trial. The results of the study will probably be published at the end of 2023.

READ MORE ABOUT PLACEBOS

In their 320 page book, Prof. Dr Ulrike Bingel, Prof. Dr Manfred Schedlowski and Helga Kessler cast light on the subject of placebos from different and at times unexpected perspectives: they describe not only the clinical research but also placebo effects in marketing, in art and in sport in an easy-to-read style.

ISBN 978-3-906304-40-3

AN EXPECTANT IMMUNE SYSTEM

The consultation, non-verbal communication, rooms that look clean and clinical: all these can guide patients’ expectations in the right direction. By contrast, this is not the case in the field of research of psychologist Prof. Dr Manfred Schedlowski, who is the director of the Institute of Medical Psychology and Behavioral Immunobiology at Essen University Hospital. Together with his team, he is also working at CRC/Transregio 289.

Schedlowski analyses connections between the nervous, hormonal and immune systems. Amongst other things, his team is looking at the effect of learning processes on immune functions. ‘Inducing positive expectations with a consultation and a competent appearance doesn’t work here,’ Schedlowski says of the difference between his and Bingel’s areas of research. ‘On their own, impressions have no effect on the immune system. In this case, the classic conditioning is needed – a learned reaction to a very specific stimulus, like Pavlov’s famous dogs responding to the ringing of a bell.’

As an example, Schedlowski cites organ recipients. Their immune system must be permanently suppressed by medication so that it does not reject the new tissue. This is because our immune systems have a simple world view: alien = bad. Unfortunately, after a transplant this would have fatal consequences. Yet at the same time, medicines that suppress this automatic response have side-effects. ‘Just think how practical it would be if you could patch in the brain as an “auxiliary engine”, in order to reduce the active ingredient and as a result the undesirable effects,’ says Schedlowski.

Consequently, his volunteers receive a medicine that suppresses the immune system at the same time as the conditioned stimulus – a combination of optics, haptics and taste which is unknown in everyday life and will probably remain so: green-coloured strawberry milkshake with a lavender flavour.

REDUCING SIDE-EFFECTS, SAVING ACTIVE INGREDIENTS

Repeated simultaneous administration of the strawberry/lavender milkshake cocktail and the medicine leads the brain – which communicates regularly with the immune system using neuroanatomical and biochemical compounds – to associate it with the effect of the medicine: regions of the brain such as the insular cortex and amygdala process the unique stimulus and transmit it to the organs of our endogenous defence – the spleen or lymph nodes, where the immune response of key cells are blocked. The researchers have already partially identified this cascade, but there are presumably also others that ensure that a flavour signal without active ingredient triggers the desired effect.

‘To begin with it works well; unfortunately the conditioning effect fades with time,’ reports Schedlowski, ‘However, our studies have shown that we can prevent this forgetting or at least delay it if we add small quantities of the medicine to the flavoured stimulus.’ The process can reduce side-effects and save on expensive active ingredients. ‘We want to stabilise these effects so that we can use them in daily clinical practice to treat patients.’

Not only subjectively perceptible symptoms, but also measurable values and physiological functions: expectations can make the difference to therapeutic success here. Bingel puts it like this: ‘In recent decades, we have focused so much on biomedical details that we forgot the supposed soft factors. Yet positive experiences, expectations and pharmacologically effective medicines can be the beginning of a great alliance.’

Main image: © Binglellab