In Brief

A summary of key news

Good news for our paluno research group on secure software systems: the Collaborative Research Centre CROSSING has been approved in the third funding round. Prof. Lucas Davi is principal investigator of two projects aiming to ensure the reliability of large cloud systems and smart contracts. Since October 2014, more than 65 scientists nationally have been working in CROSSING on cryptography-based security solutions that meet the demands of computing environments of the future.

Besides efficiency and security, however, usability is also a factor: It should be possible not just for cryptography experts but also people who are involved in software development or administration or even ‘just’ end users to be able to use the solutions. In CROSSING the group has already developed new security technologies for embedded systems, smart contracts and trusted execution environments. To this end, Davi and his team are focusing on ‘attestation,’ i.e. proving that components are secure and trustworthy. ‘Attestation checks the state integrity of a system, e.g. whether software or hardware in a component has been manipulated by hackers,’ explains Davi.

In the third phase of the project he wants to address more complex software environments. ‘Our aim is to enable attestation for large-scale, distributed computing systems and cloud applications.’

Neither friend nor enemy? Not male or female? How do people cope with situations in which familiar differentiators no longer work? This is what the Research Unit ‘Ambiguity and Distinction. Historical and Cultural Dynamics’ is investigating. Their timespan covers the period from the late Middle Ages to the present day, while geographically they look at populations spreading from Asia to Europe and Africa and on to America. The German Research Foundation (DFG) has provided the project with three million euros for another three years.

Ambiguity, i.e. uncertain meaning, occurs where distinctions that help to order the social world no longer fit. ‘This gives rise to new forms of order, which in turn lead to new ambiguity,’ explains historian Prof. Benjamin Scheller, project speaker.

So how did people cope with such uncertain relationships in different epochs and cultures? How could they structure their world when everything was changing? And how can we do so now? As an example, Scheller cites reporting about transgender and gender alignment in the German media: here, ambiguity was initially used to attract attention and provoke the supposed order of two genders. Since then, the position that there are more than two genders has prevailed – so the observation of ambiguity led to an adjustment having to be made.

To protect the environment and be less dependent on imports we need electricity from fossil fuels to disappear from the production chain where possible. The Federal State of North Rhine-Westphalia is promoting this goal with 5.3 million euros to establish a Power-to-X test platform at the UDE. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries is the overall coordinator. Other project partners are Evonik Industries and the Fraunhofer UMSICHT.

The problem is well-known: it is difficult to store energy from wind, hydroelectric or solar generators. One solution is to use the ‘excess’ to make storable products that can be used when needed. This process is called Power-to-X. ‘In real terms that means this project will produce synthetic fuels or climate-neutral chemicals, including from CO2 which arises during industrial processes anyway,’ explains scientific head of the project Prof. Klaus Görner from the UDE. Co-electrolysis and plasmalysis are the buzzwords: using energy from renewable sources, climate-neutral chemicals that are important in the production of fuels are created from water and the greenhouse gas. The facilities necessary for this are being built at the Chair of Environmental Process Engineering and Plant Design in Essen.

Who do Germans with a migrant background vote for? What are their political attitudes? For the second time a research unit led by Prof. Achim Goerres and Prof. Sabrina J. Mayer is studying these questions, and, as in the first round four years ago, the research was triggered by the German elections. The Immigrant German Election Study II (IMGES II) will be funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) until 2024.

Thanks to Big Data technology, the mountain of data in the election study, which is based on telephone interviews, is huge. The study was designed to be representative of a metropolis, that is, Duisburg. It is therefore possible to analyse in detail the role of the social and political environment of survey participants in casting their vote.

There are already significant results: for instance, survey participants are satisfied with democracy and feel that they are Germans. They also vote similarly to people who do not have a history of migration. The pattern that stood for decades that Russian Germans vote CDU, while those with Turkish origins vote SPD is no longer true. ‘The party affiliations that we could observe in 2021 for voters with Turkish, Russo-German or other post-Soviet roots have increasingly merged with those who have no history of migration,’ says Goerres. Voter turnout was also almost identical.

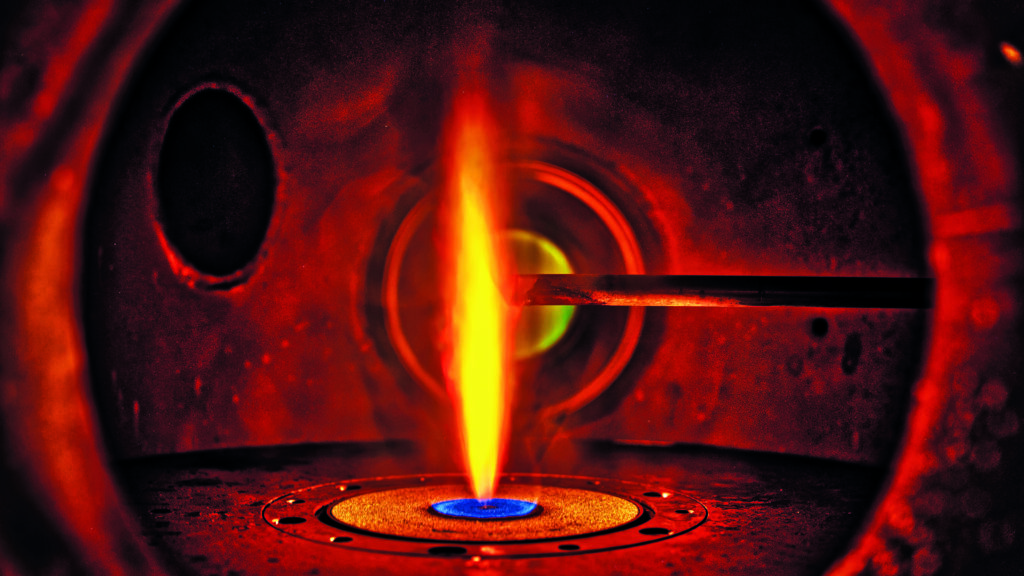

View of the centre of a synthesis reactor, in which nanoparticles are created and studied within a spray flame. | © Samer Suleiman

Almost all everyday items come into contact with at least one catalyst in the course of production, as they make the process cheaper, more environmentally friendly or even simply possible. The development of more affordable, highly active and selective catalysts at atomic level is the objective of the Collaborative Research Centre/Transregio (CRC/TRR 247) ‘Heterogeneous Oxidation Catalysis in the Liquid Phase – Mechanisms and Materials in Thermal, Electro-, and Photocatalysis’.

Following a successful first phase, funding has been extended by the German Research Foundation (DFG) for four years and the centre is receiving another 12.3 million euros. The researchers will now be working to identify active centres of the materials and to understand how the response mechanisms work in detail. The Ruhr University Bochum is leading the project; co-speaker is Prof. Stephan Schulz from the Institute of Inorganic Chemistry at the UDE.

Nothing works in life without compromises – but how can they be successful? And what are the limits to compromise? An interdisciplinary research network led by the UDE is fathoming out these questions. The project ‘Cultures of Compromise,’ launched in June, is being funded with 2.1 million euros by North Rhine-Westphalia for three years. The Universities of Münster and Bochum are also involved. The goal is to establish a long-term field of research.

Compromises are essential for our modern societies to function. Yet at the same time, concerns are growing that the ability and willingness to do so are diminishing. So the new network wants to research systematic knowledge of the social, political and cultural conditions necessary for compromise comparatively across cultures and times.

‘In this way we’re responding to the social need for practical and reflective knowledge,’ says Prof. Ute Schneider from the Historical Institute. ‘In this new area we want to study characteristics and variants, contexts and practices, the necessary social, political and cultural conditions, but also the duration and stability as well as effectiveness and limits of compromises.’ The UDE will be mainly contributing its expertise in historical, literary and Asian studies to the alliance.

Whether in medical diagnosis, battery storage or electrocatalysis, there are many uses for functional materials made from inorganic nanoparticles – if production processes are sufficiently researched and can be scaled up.

Precise adjustments in the nanometre range can enable control of the optical, electrical, catalytic and magnetic properties of these materials, depending on the desired application. This is what the German Research Foundation (DFG) Research Unit FOR 2284 is working on. Its objective: to develop systematic rules for design in order that complex nanoparticles can be precisely manufactured in the gaseous phase. The project has been extended until 2024 and is receiving a further 1.8 million euros.

Speaker Prof. Christof Schulz, head of the Institute for Combustion and Gas Dynamics (IVG), is pleased with their success to date: ‘We’ve succeeded in tying in fundamental research into elemental reactions and the first stages of particle formation right up to the development of system concepts that enable transfer into industrial application.’ The group is now working on increasing the complexity of target materials based on these findings. Nine Research Unit projects are located at IVG and at the Department of Electrical Engineering at the UDE as well as at The Institute of Energy and Environmental Technology.

Oncology is one of five focal areas of research in the Faculty of Medicine and at University Hospital Essen. In recent months, this research has attracted large amounts of new funding.

For example, the German Research Foundation (DFG) is providing seven million euros funding for a postgraduate programme involving the UDE teams from both the Faculties of Medicine and Biology. The aim is to investigate the mechanisms behind the individual sensitivity to radiation of different types of tumour and tissue. This is because although radiation remains one of the most effective treatments, people respond differently to it and there can be undesirable side-effects. RTG 2762 ‘Heterogeneity, Plasticity and Dynamics of the Response of Cancer Cells, Tumor and Normal Tissues to Therapeutic Radiation in Cancer’ is headed by Prof. Verena Jendrossek.

Meanwhile, the Clinical Research Unit PhenoTImE looks at tumours that successfully defend themselves against established cancer treatments and medications. Led by Prof. Dirk Schadendorf and Prof. Alexander Rösch, the teams focus on the particularly malignant melanoma as well as on aggressive tumours in the brain and pancreas. They have discovered that these types of tumour have similar survival strategies. Some cancer cells also have a very dynamic ability to change their appearance. The promising results of this research have led the German Research Foundation (DFG) to renew funding for three years and provide the unit with another nearly four million euros.

Lastly, as part of the SATURN³ network, the UDE scientists are searching for the reasons for therapeutic resistance occurring in particularly dangerous types of cancer. They want to find new ways to improve the fight against resistant tumour cells in bowel, pancreatic and especially aggressive forms of breast cancer. Analysis of the tumour material uses single-cell analysis and Artificial Intelligence. The German Ministry of Research is funding SATURN³ for five years with over 15 million euros. The network’s coordinator is Prof. Jens Siveke from the German Cancer Consortium (DKTK) and Essen University Hospital’s West German Tumor Center (WTZ).

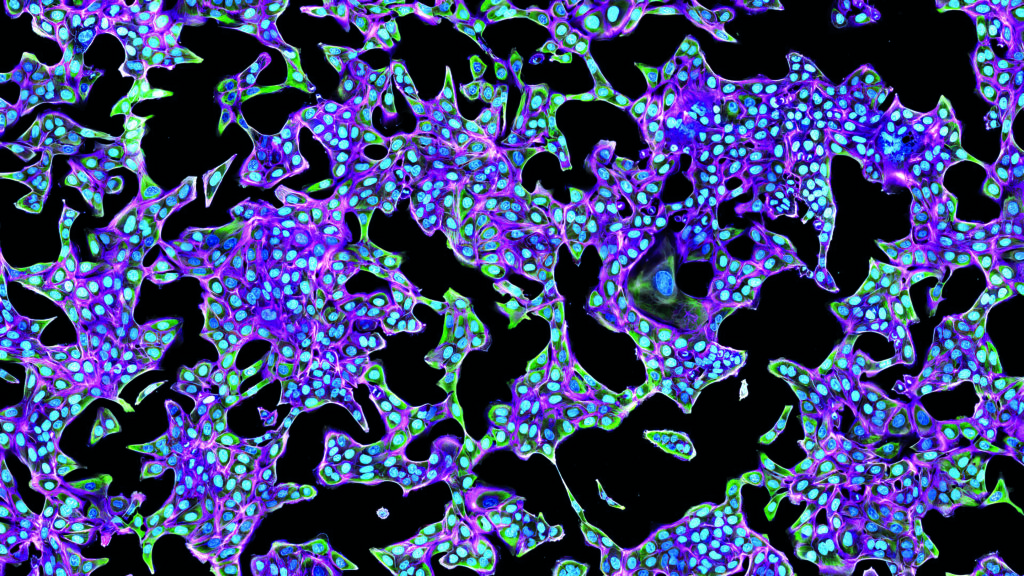

Cells have to proliferate so that an organism can develop and regenerate. This involves passing through numerous precisely defined states in succession. Transition from state to state is triggered by molecular signals and regulator switches working together. The interdisciplinary team in the Collaborative Research Centre (CRC) ‘Molecular Mechanisms of Cell State Transitions’ (SFB 1430) wants to decode how this interaction functions. It is still insufficiently understood, however, it is a crucial part of cell growth and division and as a result can be a decisive factor in the occurrence of cancer.

Hemmo Meyer (speaker) and Michael Ehrmann, each Professor at the Center of Medical Biotechnology (ZMB), are heading the CRC, which will receive around ten million euros from the German Research Foundation (DFG) until 2025. The Faculty of Medicine and five other research institutions are also involved.

‘Our scientific work starts where conventional approaches have reached their limits,’ says Meyer. ‘Therefore this cooperation of researchers from biology, chemistry and oncology is especially suited to achieve real conceptual progress in the understanding of molecular mechanisms and discovering innovative therapeutic strategies.’

CRC 1430: Steady state of the cytoskeleton of osteosarcoma cells (magenta: actin; green: microtubules; blue: DNA) | © ZMB/ICCE

Where does racism evolve, how is it spread and in what circumstances can it be reduced? The Discrimination and Racism network is seeking answers to these questions. The project is under the auspices of the Interdisciplinary Centre for Integration & Migration Research InZentIM at the UDE. Researchers from the six participating institutions want to go beyond individual observations and are working with Big Data analyses of regional and national daily newspapers and social media platforms, amongst other things. They are especially interested in the economic consequences of discrimination and racism, as well as the effectiveness of political measures.

Another cooperation project which is already under way and which InZentIM is also in charge of, is being expanded into a collaborative project. ‘The Democracy of Postmigrant Society’ researches the political preferences in immigrant society and how migrant stakeholders and those perceived as such engage politically. Questions include: Do people feel that they are represented by politicians? Do aspects like age, gender or a history of migration play a role? Does it make a difference if representatives have a ‘migrant background’ themselves?

Both projects are receiving a total of five million euros from the Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Senior Citizens, Women and Youth (BMFSFJ) and will run until 2024. With this, the German Center for Integration and Migration Research (DeZIM) will be a key player in realising the German government’s cabinet decision to fight right-wing extremism and racism.

Two-dimensional materials are extremely thin and in some cases consist of only one single layer of atoms. They are especially interesting because they have unique electrical and optical properties and their great mechanical stability means they can be rolled, folded or stretched. The new international postgraduate programme 2D-MATURE (GRK 2803) at the Faculty of Engineering with the participation of the Faculty of Physics will be tackling two questions: how can large quantities of two-dimensional materials be produced and how do they behave when combined with other materials, in such a way that they can be used in products?

The aim is to develop new methods and processes enabling industrial-scale applications, e.g. in light diodes or batteries. The programme is headed by Prof. Gerd Bacher and is receiving roughly seven million euros from the German Research Foundation (DFG). The doctoral candidates researching at the Center for Nanointegration Duisburg-Essen (CENIDE) will be cooperating with Canadian colleagues at the University of Waterloo.

Our bodies wouldn’t stand a chance against environmental germs if it weren’t for highly-specialised immune cells. One especially important type is neutrophil granulocytes, or neutrophils for short. They represent the largest share of the body’s own cellular immune defence. A new Collaborative Research Centre/Transregio TRR 332 is investigating their development, function and behaviour. The Medical Faculty is involved in five of eighteen subprojects. Teams led by Prof. Matthias Gunzer are studying precisely how neutrophils identify and destroy hostile microorganisms, how they influence the growth of tumours or can make strokes worse. The German Research Foundation (DFG) is providing 11.5 million euros in funding to the group, with 3.2 million euros going to the UDE.

Wind farms, photovoltaic plant and tidal power stations supply electricity sustainably – but not consistently. So the key problem that needs to be solved is how to store energy that is not needed when it is produced. One very promising option is Carnot batteries, which store energy in the form of heat. Now, the GermanResearch Foundation (DFG) is launching a new priority programme (SPP) under the aegis of the UDE, and is providing around 2.5 million euros a year for it from 2023.

A Carnot battery stores energy as heat in affordable materials such as water, stone or in the form of molten salts. When needed, it is then converted back into electrical energy, i.e. electricity, by means of steam turbines, for example. Although the principle has been known for a long time, until now there has hardly been any reliable data about efficiency, costs or even just practical potential applications for energy storage.

The priority programme ‘Carnot Batteries: Inverse Design from Market to Molecule’ (SPP 2403) wants not only to close this gap with its fundamentally new approach using the top-down method, but to surmount it with the best possible end result.

‘With economists, we analyse what’s actually needed and search for the physical and technical possibilities and limits,’ affirms Prof. Burak Atakan, head of Thermodynamics at the Institute for Combustion and Gas Dynamics and speaker of the newly-established SPP 2403. ‘Then step-by-step we will go deeper into the details, determine the best-possible system, suitable circuitries, appropriate substances and their ideal combinations – in order finally to develop the optimal Carnot battery.’